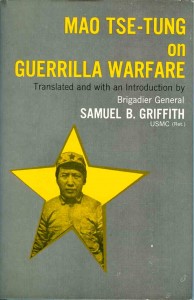

Here at WoWasis, we’d guess that the collective United States military never got around to reading Mao Tse-Tung’s 73 page Yu Chi Chan, an expert treatise on the art of guerilla war, before it got hopelessly bogged down in the quagmire called Vietnam. Translated brilliantly by Brigadier General Samuel B. Griffith, USMC (Ret.) as Mao Te-Tung on Guerilla Warfare and published in 1961, it also contains an important and insightful 31 page analysis written by the translator, who would appear to be practically begging the U.S. not to become embroiled in guerilla war, led by Mao military disciple Ho Chi Minh, who had prior success, strategically and tactically, against the French.

Here at WoWasis, we’d guess that the collective United States military never got around to reading Mao Tse-Tung’s 73 page Yu Chi Chan, an expert treatise on the art of guerilla war, before it got hopelessly bogged down in the quagmire called Vietnam. Translated brilliantly by Brigadier General Samuel B. Griffith, USMC (Ret.) as Mao Te-Tung on Guerilla Warfare and published in 1961, it also contains an important and insightful 31 page analysis written by the translator, who would appear to be practically begging the U.S. not to become embroiled in guerilla war, led by Mao military disciple Ho Chi Minh, who had prior success, strategically and tactically, against the French.

Mao’s book was originally produced in 1937 as a series of pamphlets mandating how a guerilla war should be planned, led, and fought, in this case against the Japanese. The tenets, though, can apply to any country, and time, any place (in his introduction, Griffith discusses Francis “Swamp Fox” Marion’s guerilla tactics again the British during the Revolutionary War fought in what is now the United States). What Mao continually stresses is having non-combatants being complete believers in the guerilla action, to the extent that they support guerilla fighters by willfully proving food, shelter, and transportation when necessary. To this effect, Mao’s political officers were as important as the fighters, carrying the message to the people and fighters alike, discussing topics such as colonialism, land reform, and politics in discussion groups.

In terms of fighting, Mao describes how guerilla fighting differs from conventional warfare:

What is basic guerrilla strategy? Guerrilla strategy must

be based primarily on alertness, mobility, and attack. It

must be adjusted to the enemy situation, the terrain, the

existing lines of communication, the relative strengths, the

weather, and the situation of the people.

In guerrilla warfare, select the tactic of seeming to come

from the east and attacking from the west; avoid the solid,

attack the hollow; attack; withdraw; deliver a lightning

blow, seek a lightning decision. When guerrillas engage a

stronger enemy, they withdraw when he advances; harass

him when he stops; strike him when he is weary; pursue

him when he withdraws. In guerrilla strategy, the enemy’s

rear, flanks, and other vulnerable spots are his vital points,

and there he must be harassed, attacked, dispersed, exhausted

and annihilated.

Mao also includes a number of “Rules and Remarks” that promulgate important behaviors when in the field as they relate to local inhabitants:

Rules:

1. All actions are subject to command.

2. Do not steal from the people.

3. Be neither selfish nor unjust.

Remarks:

1. Replace the door when you leave the house.

(doors were typically lifted off hinges and used as beds)

2. Roll up the bedding on which you have slept.

3. Be courteous.

4. Be honest in your transactions.

5. Return what you borrow.

6. Replace what you break.

7. Do not bathe in the presence of women.

8. Do not without authority search the pocketbooks

of those you arrest.

From the perspective of the West — and particularly that of the United States — perhaps the most cogent elements are found in Griffith’s introduction, which bears re-reading after Mao’s text. Here, Griffith explains the reasons many people feel that revolutionary military action is a necessity:

A potential revolutionary situation exists in any country

where the government consistently fails in its obligation to

ensure at least a minimally decent life for the

great majority of its citizens. If there also exists even the

nucleus of a revolutionary party able to supply doctrine and

organization, only one ingredient is needed: the instrument

for violent revolutionary action.

In many countries, there are but two classes, the rich

and the miserably poor. In these countries, the relatively

small middle class—merchants, bankers, doctors, lawyers,

engineers—lacks forceful leadership, is fragmented by un-

ceasing factional quarrels, and is politically ineffective. Its

program, which usually posits a socialized society and some

form of liberal parliamentary democracy, is anathema to

the exclusive and tightly knit possessing minority. It is also

rejected by the frustrated intellectual youth, who move

irrevocably toward violent revolution. To the illiterate and

destitute, it represents a package of promises that experi-

ence tells them will never be fulfilled.

People who live at subsistence level want first things to

be put first. They are not particularly interested in freedom

of religion, freedom of the press, free enterprise as we

understand it, or the secret ballot. Their needs are more

basic: land, tools, fertilizers, something better than rags

for their children, houses to replace their shacks, freedom

from police oppression, medical attention, primary schools.

Those who have known only poverty have begun to wonder

why they should continue to wait passively for improve-

ments. They see — and not always through Red-tinted

glasses — examples of peoples who have changed the struc-

ture of their societies, and they ask, “What have we to

lose?” When a great many people begin to ask themselves

this question, a revolutionary guerrilla situation is incipient.

This short book can be read in one sitting, and Griffith’s short but important analysis is a key element. Reading it should be a prerequisite to any military group wishing to wage war in another country where significant numbers of the indigenous population are not reaping proper and deserved benefit from the government being supported. Buy this book now at the WoWasis eStore.

Leave a Reply