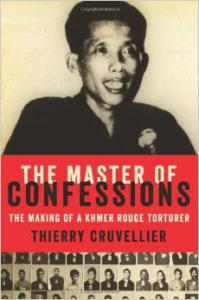

It’s tempting to stop reading about the reign of terror in Cambodia, led by the Khmer Rouge. The major statistic, an estimated quarter of the nation’s population murdered, is well-known. It’s the why of it that leaves us here at WoWasis, along with the rest of the world, perturbed. That’s where French author Thierry Cruvellier’s The Master of Confessions: The Making of a Khmer Rouge Torturer (2011, ISBN 978-0-06-232954-7) comes in. For it climbs into the mind of Kaing Guek Eav, known as “Duch,” who headed the notorious S-21 concentration camp, perhaps better known as Tuol Sleng prison.

It’s tempting to stop reading about the reign of terror in Cambodia, led by the Khmer Rouge. The major statistic, an estimated quarter of the nation’s population murdered, is well-known. It’s the why of it that leaves us here at WoWasis, along with the rest of the world, perturbed. That’s where French author Thierry Cruvellier’s The Master of Confessions: The Making of a Khmer Rouge Torturer (2011, ISBN 978-0-06-232954-7) comes in. For it climbs into the mind of Kaing Guek Eav, known as “Duch,” who headed the notorious S-21 concentration camp, perhaps better known as Tuol Sleng prison.

Cruvillier’s book is based on Duch’s testimony before Cambodia’s United Nations-backed Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC), held between February and November of 2009. It’s more than a tale of “I was just doing my job, as odious as it was” which was essentially Duch’s position in court. His fascinating testimony describes how a phalanx of school teachers — including legendary torturers Mam Nai (Ta Chan) and Tang Sin Hean (Comrade Pon) — adopted a Cambodian form of Maoist Communism to rid their country, first of anyone who had dealings with Westerners, and then of people sharing their own philosophy. Three-quarters of the estimated 14,000 people tortured at Tuol Sleng and soon murdered were Khmer Rouge themselves, purged in a sordid tribute to Stalinism.

There’s plenty to reflect upon in this 326 page book (in a remarkable oversight, there is no index; it badly needs one). Three of its most cogent concepts are those surrounding the nature of Communism, the importance of secrecy as a weapon of control, and whether or not the mortifying deeds described in the book are those of a monster or a rational human being. Early on, the author ruminates about the act of the vilification and ultimate murder of a specific class — rather than an ethnicity —- of people:

Duch’s is the first international trial concerned with crimes committed in the name of Communism. International lawyers and human rights activists are scathing about so-called

nationalist revolutions-those that openly pursue racist or xenophobic aims. No one has any trouble rejecting the movement for a Greater Serbia or denouncing Hutu Power. Yet many balk at the notion that, in a trial of the Khmer Rouge, Communism itself takes the stand as well.

When right-wing revolutions conflate purity with race, the violent resulting ideology is cause for alarm; yet when a left-wing revolution conflates notions of purity with class, it is somehow deemed appealing. Desiring a single race of men is a hateful project; desiring a single class of men (or two, or four), a good intent.

To create the “final solution,” through, a certain degree of secrecy must be maintained while it’s being accomplished:

Secrecy: nothing was better maintained than secrecy. So precious was secrecy to the Khmer Rouge leadership that for a long time the Party’s very existence was kept hidden, and the name of Brother Number One, Pol Pot, wasn’t divulged until more than a year after the 1975 victory, and then only discreetly.

“I was instructed to share nothing with my colleagues,” remembers Prak Khan. “I was told to keep everything secret. Each of us had to keep things secret. We were supposed to look after only those things that concerned us, or else we would be reported.”

Duch taught his staff that secrecy was the very soul of their mission and that, without it, their work made no sense. Guards and interrogators were not authorized to communicate with other units. Merely having contact with the outside world was deemed suspicious. Secrecy was an obsession, the Party’s alpha and omega. It was also a formidable instrument of control that, like everything else in Democratic Kampuchea, eventually imposed its own insane logic over all other lines of reasoning. The systematic execution of prisoners at S-21 was in large part due to the absolute imperative of keeping the prison secret. Due to secrecy becoming of utmost importance, it was decided that nobody could get out alive. And if someone were arrested by mistake, then the secrecy of the institution took precedence over that man’s life.

The author, reminiscent of filmmaker Alain Resnais’ ‘Night and Fog,’ Nazi concentration camp film, waxes almost poetic in his descriptions of the famous photographs in Tuol Sleng:

But it is the photographs of the prisoners that anchor the experience of visiting S-21. Around two thousand portraits are exhibited in what were once classrooms, then prison cells, and now museum rooms. Their subjects look frightened, questioning, restless, quiet, defiant, smiling, tired, swollen, puffed up, gentle, jocular, determined, shocked, stiff, confident, obedient, despondent, resigned, evasive, astonished, sweet, sad, anxious, exhausted, proud. They are young, old, good-looking, ugly, baby-faced, thin, plump, blindfolded, and tied up. There is nothing more crushing than seeing these portraits hung tightly together, panel after panel, room after room. The intellectual power, emotional charge, documentary, and even artistic value of these snapshots of the thousands who died in the days or weeks after their photos were taken are what both define and anchor memory at S-21.

Yet almost everyone who visits S-21 walks past the photographs of its victims utterly unaware of the ambiguity inherent in many of them, including in the famous, harrowing image of a beautiful woman, understated and elegant, her hair slightly disheveled, her expression one of exhaustion, despair, and resignation, who is holding on her knees a sleeping infant in diapers, its eyes closed and hair slick with sweat. This woman, who was murdered in 1978 at S-21, was herself a revolutionary, the wife of the secretary of the southeast region, one of the regime’s high officials who fell from grace and was eliminated, along with his family, by the regime he had served.

And in the countryside surrounding Anlong Veng, the final resting spot of Pol Pot:

For a long time, the road to Anlong Veng was sufficiently rough and corrugated by rain to dissuade most visitors, including most tourists, from venturing there. The sleepy, remote little town lies at the foot of the Dangrek Mountains on Cambodia’s northern border. Its location appears to serve a dual purpose: on the one hand, it is protected from Thailand by the mountains, but on the other hand, it provides easy refuge.

Just before the bridge leading into town, a track veers off to the left. The track leads three hundred meters out onto a small peninsula covered in mango trees and jutting out into an area that is both land and water, known locally as “the lake.” The subtle, muted combination of water, wild grasses, and tall, bare trees soaring spear-like into the sky infuses the area with a meditative peace. If you stand on the peninsula and look out over this marsh, you can see the village of Anlong Veng without being seen from it. This promontory suits wise men, thinkers, and soldiers on watch, and it’s here that Ta Mok, the most powerful and brutal of Khmer Rouge military commanders, lived.

Thierry Cruvellier really leaves no stone unturned, here. Duch’s fear of Ta Mok is described and there are nearly full chapters on people such as François Bizot, author of ‘The Gate,’ and one of the few European survivors of Duch’s ministrations, and Ta Chan, that most rigorous of interrogators.

Ultimately, what is the reader left with? After a disagreement among his lawyers, Duch received a life prison sentence. His testimony, in essence, can be described as a textbook for mass murder as codified by the state. The word ‘sadism’ isn’t mentioned in the book. Although Duch presided over the terror that occurred inside S-21, Ta Chan and Comrade Pon were ultimately the most significant “hands-on” torturists. At any rate, the author avoids sensationalism as much as possible, enough so that there are no photographs in the book. What’s written in words is terrifying enough.

The country of Cambodia is still in recovery over its Khmer Rouge era. The historical record has been accurately described by writers such as David Chandler. But the psychology of how intelligent and rational people such as Duch dehumanized themselves in search of an idealistic goal has been given perhaps the most powerful voice by Thierry Cruvellier.

Buy this book now at the WoWasis eStore.

Leave a Reply