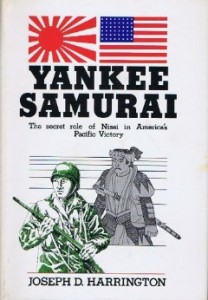

Author Joseph D. Harrington has written an informative and insightful history of the Nisei (Americans of Japanese Ancestry, or AJAs, the first generation to be born outside of Japan, and children of Issei, their Japanese-born parents living in the United States), working for the U.S. armed forces in the Pacific during World War II. Yankee Samurai: the Secret Role of Nisei in America’s Pacific Victory (1979) is no whitewashed narrative, as it exposes U.S. internment camps, prejudices, and the frustrations of patriotic Japanese-Americans who wanted to fight for their country, but were initially rebuffed. As the book relates, not all Nisei were in favor of fighting, and even those that did encountered another kind of prejudice at first, from Hawaiian-born Nisei who more than occasionally felt that continental Japanese-Americans just didn’t measure up, linguistically-speaking.

Author Joseph D. Harrington has written an informative and insightful history of the Nisei (Americans of Japanese Ancestry, or AJAs, the first generation to be born outside of Japan, and children of Issei, their Japanese-born parents living in the United States), working for the U.S. armed forces in the Pacific during World War II. Yankee Samurai: the Secret Role of Nisei in America’s Pacific Victory (1979) is no whitewashed narrative, as it exposes U.S. internment camps, prejudices, and the frustrations of patriotic Japanese-Americans who wanted to fight for their country, but were initially rebuffed. As the book relates, not all Nisei were in favor of fighting, and even those that did encountered another kind of prejudice at first, from Hawaiian-born Nisei who more than occasionally felt that continental Japanese-Americans just didn’t measure up, linguistically-speaking.

Like other children of immigrants, the Nisei were, to a large extent, caught between Japanese tradition and U.S. culture. The concept of honor, an essential element in Japanese-American family life, ended up serving U.S. military interests well:

A good Nisei obeyed father, while hoping with all his heart never to disappoint mother. Behavior expectations were based on Confucian morality. Loyalty to country, respect for parents, and maintenance of harmony in family and other personal relationships were paramount. These topped all considerations a Nisei might entertain. Issei fathers could never digest so radical a concept as human rights. These had no place in the scheme of things. The race, the group, the family came first. The individual came last, if indeed he got any consideration at all, which was not likely. Living consisted of observing one’s obligations, not dreaming of entitlements. A well-reared Nisei’s life was guided by theprinciples of on, gimu and giri. On was a moral debt one owed nation, parents and teachers, from whom all blessings were known to flow. The nature of on was such that the debt could never be fully repaid, and was therefore lifelong. Gimu covered moral and legal duties. It required that every Nisei be a good American, a good student, a good worker; that he honor and obey his parents; and that he meet all responsibilities. Giri worked in the social area, with moral overtones. A Nisei had to be meticulous about repaying all favors, gifts, and help provided by anyone. He dared not bring haii (shame) on his race, family, or even neighborhood by breaking the law or committing other unworthy acts. Failing in school was unforgivable. Also, a Nisei had to neglect or overlook no opportunity for bringing honor on his family, so that it might have pride. Everything was based on self-abnegation. Teachings, sayings and stories from an age-old culture illustrated each major and minor point.

These concepts were the hallmarks of Nisei serving in the U.S. military, allowing them to excel in spite, or perhaps as a reaction to the internment of their families on U.S. soil. The book begins by describing the Military Intelligence Service Language School and discusses the challenge of Nisei having to learn Japanese as spoken in Japan as well as the complicated nuances of Japanese writing, of which three forms needed to be translated from purloined or intercepted documents:

Kaisho. The printed version of Kanji. In various forms, it is used for most publications, which can only be read by someone who has memorized a great number of ideographs. For Americans, a formidable barrier.

Gyosho. Hand-written Japanese. Comparable, although not precisely, to the Palmer Method of Penmanship the author and his peers had to master in pre-war grammar school. Very difficult for Americans.

Sosho. More or less a shorthand rendering of Kanji, called “grass writing.” Highly individualized. Almost impossible for an American to master. Most Japanese Army field orders were taken down over a telephone in sosho. The ability to translate rapidly this personalized “scribbling” from documents seized near the front was the most potent weapon in the arsenal of a linguist.

As the author notes, it was usually Kibei (AJAs who had been sent to Japan, as youths, by their parents to learn Japanese) who proved best at deciphering sosho. Kibei, like other Nisei, who’d been kicked out of the Army early on, had to be found, approached, and asked to join again. Many of them were interned in stateside camps.

A main objective of Harrington’s book is to do his best to ensure the names of Nisei contributors to the U.S. war effort are not forgotten. As he points out, Nisei didn’t brag about their efforts, and tracking down dozens of war heroes thirty years after the fact was an exhausting effort. Poignantly, many of the most outstanding Nisei servicemen never received a battle award. When they were photographed at work, the military made them turn their heads so that they couldn’t be identified, thus helping to prevent relatives in Japan from being arrested and tortured. The author has done an outstanding job of uncovering names and telling little-known stories. Especially fascinating are the ones that describe the analytical acumen of Nisei translators, as with this one regarding comfort women:

A main objective of Harrington’s book is to do his best to ensure the names of Nisei contributors to the U.S. war effort are not forgotten. As he points out, Nisei didn’t brag about their efforts, and tracking down dozens of war heroes thirty years after the fact was an exhausting effort. Poignantly, many of the most outstanding Nisei servicemen never received a battle award. When they were photographed at work, the military made them turn their heads so that they couldn’t be identified, thus helping to prevent relatives in Japan from being arrested and tortured. The author has done an outstanding job of uncovering names and telling little-known stories. Especially fascinating are the ones that describe the analytical acumen of Nisei translators, as with this one regarding comfort women:

Comfort girls may have had some Nisei wondering whether the enemy’s ideas on how to wage war might be more compatible with the average infantryman’s wishes, but the linguists did turn use of them against the enemy. A document, picked up on Guadalcanal, helped. Later discovered to be in the gosho handwriting of a senior Rabaul staff officer, it was the officers’ and enlisted men’s schedule – with prices – for use of comfort girls at the New Britain base. It listedhours for each, and even had the menstrual period for each girl plotted, so that a customer could decide upon the day, as well as the hour.

This document was thoroughly analyzed, to develop when the maximum number of senior officers would be patronizing the girls. An air strike was then laid on for that hour. After that, according to John Anderton, “Japanese leadership at Rabaul was never the same.”

This book has appeal to a wide audience, but will be of particular value to Nisei and Sansei (children of Nisei) wishing to know more about the extraordinary contributions made by Nisei to the United States’ success in World War II.

[…] first became aware of Japanese submariner Zenji Orita in author Joseph D. Harrington’s book Yankee Samurai: the Secret Role of Nisei in America’s Pacific Victory (1979), which sent us scurrying to find Orita’s book I-Boat Captain: How Japanese Submarines […]

Very interesting article. I was close friends with a Japanese born couple. They adopted a son from Japan. The son was expected to do very well in school. This included after school activities like music and sports. He eventually went to college. But the pressure of school was too much. And he didn’t want to let his parents down. He didn’t want to bring shame to his family. So he committed suicide. He felt there was no way out. I wish there was more of a balance in that culture. It’s just sad.