There are quite a few books written on prisons in Asia, from Kang Chol-hwan’s sobering Aquariums of Pyongyang to Steve Raymond’s Poison River.

There are quite a few books written on prisons in Asia, from Kang Chol-hwan’s sobering Aquariums of Pyongyang to Steve Raymond’s Poison River.

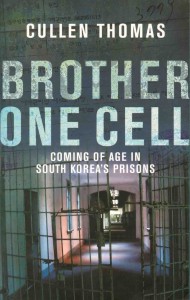

In such books, though, there is little in the way of hope or redemption. And that’s what makes Cullen Thomas’ Brother One Cell: Coming of Age on South Korea’s Prisons (2006, ISBN 13-978-0-283-07025-9) so radically different and fascinating. Thomas’ three and one-half years in Korea’s Seoul Detention Centre, and Uijongbu and Taejon prisons was transformative.

He was jailed on a drug charge, and chose to make his prison experience a learning one. This book of more than 400 pages is endlessly fascinating, and never more so than in describing the gangsters that ran the prisons’ workshops with a firm yet fair hand. He describes their “genital sunflowers,” the result of informal prison body modifications that grossly increased penile size. There are no prison rapes in the book, and there is an aura of respect running in two directions, between the convicts and their jailers. During his incarceration, Thomas picks up nuances of the Korean language as well as an understanding of how Confucianism permeates Korean society, both in and out of prison. When he is finally released and returned to the United States, Thomas makes it clear that his Korean prison experience has transformed him into a better person.

There are many passages in the book that we here at WoWasis feel are worthy of quotation, but his commentary on the differences between Korean and American prisons is especially interesting:

If I had to be imprisoned, it was good fortune it was in Confucian Korea. I was told of the possibility of being transferred to the States to complete the remainder of my time. A provision on the Korean books spoke of such a chance for an American inmate after he had served one-third of his sentence in Korea. But even if the authorities on both sides had agreed to such a move I would have refused to go. The decision in my mind couldn’t have been clearer. As a prisoner in the States 1 might have been able to wear regular clothes, watch television, eat familiar food, sleep on a bed. It would have been easier for friends and family to visit me. I would have had a western-style toilet, hot water and heat in the winter, access to libraries and special facilities for exercise and recreation. No doubt my life there would have been more comfortable in many ways, more modern, physically less restrictive – but also seedier, I’m pretty sure, more decadent and more dangerous. As incongruous as it may seem, my preference was to stay in South Korea, 7,000 miles from home in a country whose modern history had been scarred by militarism, authoritarianism and a not-so-distant third-world poverty. In Korea I didn’t have to constantly think about my survival, about being raped or assaulted. While the authorities may not have reached men in their hearts or heads, and while we lived relatively bare and rough lives, we weren’t surrounded by brutality and violence. I’ve often thought about prison reform and what could be done to try to help society through the system’s opportunity with criminals. I’ve often wondered if there might be some way to take from Korea those Confucian qualities that made her prisons more humane, more civilized perhaps, than ours in the US. As if you could take a cultural eye-dropper, suck out of South Korea the good, carry it over the ocean, and drop it into America’s veins. Maybe the US could use a little shot of Confucian shame, a better sense of collective living. But you can’t inject Confucian ethics into America’s bloodstream. There’s no catalyst for it. It’s too late. Korea’s one race has been marinating in a code of behavior and propriety and well-defined roles for centuries. She lives and dies by it. There are so many races in the US, so much room to invent ways of relating, so much freelancing with behavior and language. We have no uniform code. It’s a cauldron of competing codes.

Today, Cullen Thomas is active teaching writers courses in the eastern U.S., and this book is indicative of s number of exceptional insights into both Korea and prison life. It is highly recommended. Buy it here at the WoWasis eStore.

Leave a Reply