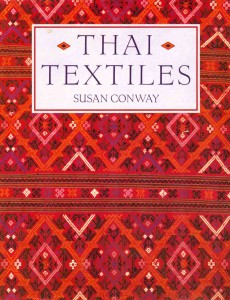

Here at WoWasis, we consider it a tribute to author Susan Conway that her book Thai Textiles (1992, ISBN 974-8225-798) continues to be a primary source on the subject some 20 years after its initial publishing date. This 192 page paperback retails for $140 USD on the internet, although used copies may be found for under $10 USD. Conway’s exacting scholarship is the keynote here. She’s knowledgeable on the craft, and weaves historical and cultural elements into the story as well, accompanied by more than 150 photos, 105 of them in color.

Here at WoWasis, we consider it a tribute to author Susan Conway that her book Thai Textiles (1992, ISBN 974-8225-798) continues to be a primary source on the subject some 20 years after its initial publishing date. This 192 page paperback retails for $140 USD on the internet, although used copies may be found for under $10 USD. Conway’s exacting scholarship is the keynote here. She’s knowledgeable on the craft, and weaves historical and cultural elements into the story as well, accompanied by more than 150 photos, 105 of them in color.

Her chapter entitled ‘Textiles, Religion and Society’ is indicative of the detail imbued in virtually every page. She describes the four main Buddhist festivals, when monks are presented with woven textiles, Khaw Phansa, Org Phansa, Bhun Kathin, and Bun Phraawes, and discusses the colors sacred to Thais, keyed to each day of the week. In her chapter on ‘Silk and Cotton Production, she discusses the home-based silk industry, and mentions a fascinating element of the production of robes for monks:

Before the advent of aniline dyes, monks’ cotton robes were dyed according to the rules laid down in religious texts. Bright colours were forbidden, and a dull yellow-brown was considered correct. This colour was achieved with dye from the Jackfruit tree, khanun (Artocarpus iniegrifolius). Before the robes were dyed they were mordanted in a preparation made from cow dung, fine mud from the river bed and plant extracts. The dye was prepared by slicing core-wood of the breadfruit tree into fragments and boiling them in water to extract the dye. The mordanted robes were immersed in the dye bath until they reached the required shade of dull yellow-brown (Suvatabandhu 1964).

Many customs and superstitions surround the use of vegetable dyes. Dye vats were prepared in a special corner of the compound away from the house, dyes were not used on Buddhist holy days, and monks were not allowed near as they were believed to weaken the strength of the dyes. Pregnant or menstruating women were also believed to affect the dye baths (Peetathawatchai 1973). Restrictions surrounding the use of mordants include not talking while preparing the ingredients.

In the past a vast range of trees, plants and shrubs were used for dyes and mordants, but today only the elderly women can identify them. With the pressure on land for cash-crops, many woodland and scrub areas have been cleared and the habitat for dye plants has been lost. It is likely that the elderly women in the villages may be the last generation to know all the ingredients.

Conway’s bibliography cites dozens of works, and as such, represents an important research tool that is as viable today as it was when the book was written. This book is a fascinating and faced-paced reading into the historical, social, and production processes partial to Thai textiles, and is recommended to any reader desirous of discovering the basics and minutiae of this important element of Thai life.

Leave a Reply