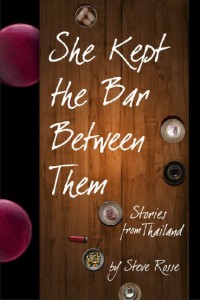

Note: this is a short story from Steve Rosse’s new book, She Kept the Bar Between Them. Read the WoWasis review of the book here.

Note: this is a short story from Steve Rosse’s new book, She Kept the Bar Between Them. Read the WoWasis review of the book here.

Pilgrimage

The lights of Bangkok’s skyline slid up the taxi’s windscreen like a meteor shower in reverse. Murray’s eyes felt cleansed by the sight of it. The sound of the tires on the freeway had a quality he’d never heard before, a drone that possibly had never existed before he noticed it. The smile of the desk clerk when he checked in was compassion made flesh, and he could have spent the rest of the night staring into that bright brown face. The amenities in his room were unrealistically solid and present; the chunky bottle of shampoo seemed heavier than it should be for its size, like an ingot of gold. There was a hypnotic thumping coming through the wall that Murray thought at first was people making love in the next room, but came to realize was in fact a pile driver on some distant construction site. Still wearing the clothes he had travelled in he crawled into bed and was amazed by the loudness of his own breathing. He couldn’t seem to catch his breath. They had warned him not to fly.

He was awakened by the brutal tropical sunlight coming in the windows. The water came out of the shower nozzle delightfully hot; the towel was as soft as fleece. In the coffee shop he ordered the free breakfast that came with his room and he ate every morsel of food. It had been two decades since the last time he’d tasted eggs or bacon. The combination of textures, silky and crisp, was a delight. The eggs were rich and the bacon biting on his tongue. The coffee was instant, bitter and acidic; he loaded it with sugar and milk but still it was strong enough to make his heart jump. He drank four cups. He snowed a blizzard of salt on the eggs, slathered butter and jam on the toast, and doused the sliced mango until it was swimming in lime juice. He smacked his lips and chewed with his mouth open. He held every forkful under his nose and took a deep sniff before he ate it. He drew stares from the other diners but he didn’t care. He walked slowly out of the coffee shop with one hand on the wall to steady himself but with a toothpick poking jauntily from the corner of his mouth. Even the toothpick tasted good.

All the streets around his hotel were lined with bars, big and small, and all of them were closed at this hour. Down every gutter paced a street sweeper in an orange vest pushing a pile of garbage with a broad sturdy broom; every sidewalk was lined with vendors’ tables. To his eyes the piles of garbage were as colorful and alluring as the piles of merchandise on the tables. The vendors sang out to pedestrians with voices that sounded like children at play. Every wall was plastered with garish advertising, giant photographs of young women holding all sorts of products close to their faces, new cars like shiny beetles, plastic kitchenware in kindergarten hues. Even the black asphalt had a sheen of oil on it that kicked back rainbows.

Above the doorways were the signs. Murray stood in the street, staring up at the signs, and let traffic go around him. The signs were all brightly painted and each had on it some kind of cartoon representation of a woman. The cartoon women were clownishly proportioned and for the most part naked. Not nude but emphatically naked, bulbous fertility totems with black hair and Asian eyes but skin as pink as flamingos. The names of the bars were the ribald playground snickers of ten-year-old boys: Pussy Galore, Hanky Spanky, Hot Licks.

Murray found a bar that was open. It was called “Sea Hag,” and the naked woman on this sign was old and ugly, rising from the sea on a broom under a pointy black hat. Murray was pleased because he recognized the joke. In Thai rhyming slang, when pronounced in the correct tones, “si hak” meant “loose cunt.” It was the only sign on the street with an adult sense of humor, and it hung over the only open door on the block. Murray threw his head back and laughed out loud. His laughter surprised him; he could not remember the last time he’d laughed out loud.

An industrial fan on a five-foot-tall pole was standing just inside the door, moving stale air out to the sidewalk. Murray enjoyed the feeling of pushing directly into the blast of humid, stinking air before sidling around the fan. Just such a fan, and a wet bathroom floor, killed Thomas Merton in his Bangkok monastery, thought Murray. He had read a lot of Merton at one point in his life, and took it all so seriously, but now the mundane mechanism of the visionary mystic’s death made him laugh again. The laughing made him gasp for breath. He staggered a bit getting to a stool at the end of the bar. He wondered if the bartender would try to shoo him away. The place was obviously not open for business. There was no music playing and the only light in the room came from some ugly white fluorescents hung overhead. Bus trays full of glassware were collected at the far end of the bar, ready to go into the back room to be washed. The stubby faceted highball glasses, upended in their red plastic tubs, reminded Murray of rows of diamonds on red velvet trays. He thought the glasses were beautiful.

Murray climbed up onto the stool. His short walk from the hotel had left him drenched in sweat and exhausted. They had warned him against over-exertion. He settled himself as he had been taught many years ago: stacking vertebra upon vertebra like bricks in a wall. Stable. Solid. Centered. His hands were flat on the bar. He felt the familiar nervous urge to bounce his right leg but fought it. He remained still and under his breath he began his mantra. Samaa arahant… samaa arahant… samaa arahant. A feeling of peace grew in him, something he had not felt in twenty years. He had never been able to meditate successfully in the States. He had too much attachment there, to job, to family, to opinions. But he was retired now, the kids were grown, he had given away all he had. In a Bangkok bar he was attached to nothing; it was easier to let go, to become nothing. He slowly closed his eyes and concentrated on his breathing. He imagined a clear glass sphere, about the size of a grape, floating in the air immediately in front of the spot between his eyebrows. He allowed the imaginary sphere to descend slowly and enter his right nostril. He followed the sphere with his attention, breath by breath, as it crept down the center of his body toward a position half-way between his navel and his coccyx, where it came to rest.

He focused on the sphere, made it solid in the core of his being, made it the anchor, the keystone of the universe, the motionless molecule at the center of the hub of the wheel. The wooden bar under his fingers felt massive as a boulder. The vinyl bar stool creaked like a cricket. The air was thick and fetid like the atmosphere over a swamp; he smelled cigarettes and beer and vomit and urine and cooking oil. He smelled perfume and semen and diesel fuel and rotting flowers. He breathed in through his mouth in an effort to taste it all. He heard dogs barking in the street in front of the bar and he could count their numbers by their individual voices. He heard lust in a rooster crowing in the alley behind the bar, he heard hunger in a mosquito whining over his head. It was only when it ceased that he noticed the pok… pok… pok of a wooden mortar and pestle. The sound was coming through the door at the back of the bar. There were plastic beads hung in that door; he heard somebody push through them and pause. Whoever it was disturbed few of the beads in passing and made little sound; it was a woman.

With his eyes still closed he waited while she considered whether to serve him or throw him out. She approached him, and by the slowness of her approach he knew she had not made up her mind. He opened his eyes just as she arrived opposite him; she kept the bar between them. He saw from her clothes and bearing that she was not a cleaning woman and not a prostitute; he assumed that she was a partner in the ownership of the bar. Her black hair shone like onyx, her skin was the color of honey. The gold at her throat and wrists glinted under the austere fluorescent light. He didn’t try to guess her age, it didn’t matter to him. She was slim and shapely and very self-assured. Murray found her instantly attractive. She was giving him a grin, the kind of grin a woman gives an impudent child.

“Hey. You. What you want?” she asked in English. He heard challenge in her voice, but it was without aggression. There was curiosity too, and invitation. He replied automatically in Thai.

“Beer Singh, Little Sister.”

She raised an eyebrow but showed no more surprise than that. Plenty of foreigners in Bangkok can order a beer in Thai. The woman pulled a wet bottle from the slush in a cooler. The label had soaked off during the night but they both recognized the brand by the shape of the bottle. She put it in a foam sleeve and placed it onto the bar, her movements so gentle there was no sound when the bottle contacted the wood. A sign of respect, which Murray rewarded with a smile.

She casually tested his fluency. “Has Grandfather eaten yet? I can send the boy for food from the street, with respect.”

“Eaten already, thank you with affection. I beg for an ash tray a little bit.”

The woman went to the bus tubs at the end of the bar and dug out a round glass ash tray. He took a brand new pack of cigarettes from his shirt pocket and tore open the top. He pulled the first cigarette from the pack and ran it through his fingers, marveling at its compact efficiency. He put it to his nose and smelled the cheap Thai tobacco. Memories came flooding back to him: voices, songs, faces, his bare feet in sand. He felt lightheaded and swayed a bit on his stool. He focused again on aligning his spine and regained his balance. There was a sharp pain beginning in his temples, which he ignored. Without thinking he tapped the butt end of the cigarette on his thumbnail and smiled at how the old movements came back intact after so long an absence. The woman wiped out the ash tray with a paper cocktail napkin before she placed it in front of him, again without making a sound. She smiled at him, and this time her smile was open and friendly and genuine.

“Grandfather likes papaya salad, with respect?”

“Grandfather used to like it very much, with affection,” he answered. At the moment he could not recall the taste of papaya salad, but he remembered what it looked like, and he remembered that it was best when served with tiny black crabs.

“I am making some,” said the woman. “When I am finished, Grandfather can eat some, if hungry.” She flashed Murray another fabulous smile, then she added, “My name is Pig.” There was a time when he had been jaded and the irony of Thai nicknames had ceased to amuse him, but he’d been away long enough that now the idea of a lovely woman named Pig made him laugh. She was delighted by his laughter and she laughed back at him. She lit his cigarette with a cheap plastic lighter, placed it on the bar next to the ashtray and left the room.

Murray looked at the sweaty beer bottle in his hand, as naked without its label as the women on the signs outside. The unflattering light in the room made very noticeable the liver spots on the back of his hand, and the thick ropy veins on his arm, puffed and swollen from too many intravenous procedures. He slowly brought the bottle up to his lips and took a first sip. He gave out a little groan. He took a long pull. He closed his eyes and held the ice cold beer in his mouth for a moment before swallowing. It hurt his teeth, but it was the best thing he’d ever tasted in his life. He kept his eyes closed and brought the cigarette to his lips. He heard the sizzle as he puffed. It was like sucking on the nipple of contentment itself. He drew the smoke into his lungs and felt every single cell in his body rejoice. Then he coughed spasmodically, gasping like a fish on the river bank. He tasted blood.

Murray let his eyes open and focus on whatever was in front of them. He saw a double rank of bottles in front of a mirrored wall almost completely covered with snapshots and postcards. The people in the photographs all looked interesting, the scenes on the postcards looked like places he’d like to visit. In fact they looked familiar, people he knew, places he’d been. He tipped his head back and took another long drink of beer. Again the crisp, grainy taste of the beer was ambrosia. He felt an ache as the cold liquid flowed down his esophagus and past his heart. He put his cigarette in the ash tray and rubbed his left bicep. He tried to calculate how many hours he’d been without his medications. He thought it was probably close to 48 hours by now. They had warned him never to go unmedicated for longer than a couple of hours. He picked up the cigarette and took another deep hit, coughing again but less this time, and laughing at himself for doing so. He slammed down another gulp of beer and this time the pain in his chest made his eyes water.

He wiped his eyes on a napkin and when his vision was clear again he looked for the Buddha shrine he knew would be somewhere in the bar. He found it on top of a glass-fronted cooler that held soft drinks and chilled moist cloths. This Buddha was in the Suppressing Evil pose, cross-legged with one hand touching the ground, the most common variation found in bars, brothels and casinos. The shelf on which the icon sat was crowded with old offerings: an empty glass that had once held tea, or whisky, or soda pop, mounds of melted candle wax, plates of withered fruit, desiccated flowers. Dusty spider webs festooned the whole thing, making fuzzy garlands from charred incense stems to the Buddha and back. The icon probably had cost somebody the equivalent of a few dollars at the local market, the shelf a couple more, and all the offerings maybe another dollar. The whole shrine could not have cost more than ten US dollars, but it was an object of holy reverence for Murray. The almost featureless face of the cheap brass Buddha was an image he’d seen in his dreams for more than two decades. It was the face he saw when he checked into his hotel. Tears ran down his cheeks but he didn’t notice them.

Murray rose from his stool and approached the Buddha shrine. He stood up on his toes and poured a little of his beer into the empty glass. He clasped his hands in front of his forehead, still holding his beer bottle, and began to recite namoddhasa. He only got as far as the second stanza before he gasped and bent over, as if somebody had given a sharp tug on a string connected to his breast bone. Murray exhaled hard through clenched teeth and pink spittle sprayed the floor. The pain was exquisite. He faltered backward to the bar and fell against it, sliding down to sit on the floor. His vision was filling up with a red haze but he tried to lift his eyes to the Buddha. The icon was covered in gold leaf now, and glittered in the light of a million candles. He tried to finish his prayer, but he could not inhale.

The second wave of red hot pain hit him like a truck. He rolled to his side, his left arm wrapped around his chest, his right hand still clutching his beer. He was aware of his wet cheek resting on the sticky floor, and he was aware of the crushing pain in his chest, shoulder and arm, but he could not feel anything else. He could still hear the pok… pok… pok… coming from the back room, and in between the poks there was a LUB and a DUB that he realized was his struggling heart. Pok-LUB… pok-DUB… pok-LUB…pok-DUB…

The pain was lessening, replaced with welcome numbness. Murray concentrated and managed to put down his beer bottle without making any sound. He noted that there was still two inches of fluid in the bottom. He raised his eyes to look at the Buddha shrine.

“We had a deal,” he whispered. “I was supposed to get a beer and a smoke.” There was a sound, not one he could identify, or even describe, though it might have been made by an electric fan, or tires on pavement. The more he noticed it, the louder it got, as the sounds from the kitchen faded away, pok… pok-DUB, pok…pok…pok-LUB… Murray looked at his nearly empty beer.

“Ah, what the hell,” he said, so quietly that it was only in his head. “Close enough.”

Leave a Reply