Books are among mankind’s most powerful inventions. Das Kapital changed the world as surely as the steam engine ever did, and with one small thesis Copernicus changed the whole universe. The list of books that have changed human existence includes Mein Kampf, Mao’s Little Red Book, The Bible, The Koran, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Origin of Species. But less well known books change individual lives every day. A young man reads All Creatures Great and Small and goes on to become a veterinarian, a young woman reads Dr. Spock’s Baby Book and cancels her wedding. Every serious reader can tell a story about how a book changed their life, and this is mine.

Books are among mankind’s most powerful inventions. Das Kapital changed the world as surely as the steam engine ever did, and with one small thesis Copernicus changed the whole universe. The list of books that have changed human existence includes Mein Kampf, Mao’s Little Red Book, The Bible, The Koran, Uncle Tom’s Cabin and The Origin of Species. But less well known books change individual lives every day. A young man reads All Creatures Great and Small and goes on to become a veterinarian, a young woman reads Dr. Spock’s Baby Book and cancels her wedding. Every serious reader can tell a story about how a book changed their life, and this is mine.

Ten years ago I was a set dresser in the New York film industry, and in 1986 I spent 13 weeks in Atlantic City, New Jersey, working on a movie called Penn and Teller Get Killed. Penn and Teller were a briefly popular comic duo who were appearing in their first (and only) feature film, and the director, Arthur Penn, had won Academy Awards for Bonnie and Clyde and Little Big Man, but was finishing his career with sorry little projects starring relative unknowns. In one scene of this awful movie Teller spends the afternoon in a movie theatre, and in order to get the establishing shots of him entering and exiting the theatre the company rented an old night club called the Apollo.

Donald Trump and the Mafia brought casino gambling into Atlantic City in the 1970’s, and in an effort to keep the punters at the tables, they either bought out or burned out every other business in town, turning America’s oldest seaside resort into a ghost town almost overnight. The Apollo was one of the businesses that refused to leave quietly, so one night in 1978 there was a fire and the Apollo closed its doors forever, after nearly 50 years of operation.

When I arrived on the scene, I had a key to the front door and instructions to find the big plastic marquee letters in a cardboard box in the attic. I let myself into a beautiful lobby carpeted in mouldering burgundy wool, and passed on into the theatre itself. Ten inches of stagnant water, left behind by the long-defunct Atlantic City Fire Department, formed a tideless and stagnant sea. Rotting cafe tables which still held glassware and ashtrays full of grotesquely bloated eight-year-old cigarette butts made an archipelago between myself and the stage. On a spectacular but soot-smudged Art Deco proscenium arch, crumbling plaster cherubim looked down with sad eyes at the velvet main curtain which hung in tatters over the bandstand.

The fire had been confined to the theatre, and as I climbed the stairs to the attic I peeked into offices and storerooms which had remained undisturbed since the owners of the building escaped to Florida with their lives and the insurance money. The dressing rooms for the musicians still seemed occupied, with post cards from home and pretty girls’ pictures taped to the mirrors, and combs, toothbrushes and dozens of tubes of hair pomade lining the counters.

When I reached the attic I found it to be an enormous loft room, and it was crammed floor to ceiling with stacks of cardboard boxes. It looked like the last scene in Raiders of the Lost Ark. Most of the boxes were labelled with a man’s name and a dollar amount, like Sam Smith $12.34 or Jack Jones $21.95. As I tore open box after box in an insane effort to find the needle in the haystack that held my precious red plastic marquee letters, I found them all full of the same sort of things that I had seen in the dressing room. In my frustration I began to kick over the stacks of boxes that had rested undisturbed all those years, and piles of clothing, shoes, magazines, post cards, letters, cosmetics, guitar picks and clarinet reeds spilled across the dusty floor.

It occurred to me that what I had discovered was a sad reminder of the gypsy life led by itinerant black musicians in the 40’s, 50’s and 60’s. A man would come with the band and play an engagement of three weeks or three days, and during that time he would run up a bar bill. When it came time to go, if his bill exceeded the money he’d earned, the management would confiscate the meagre belongings on his dressing table and put them in the attic. When and if the musician returned with the money, he got his things back. If not, they remained in the attic.

I had made a shambles of the room and hopeless confusion out of the carefully preserved effects of a hundred dead men when I noticed, in the gloom of a far corner, three boxes, larger and more sturdy than the others, marked in black ink “Marquee Letters”. I felt relief and shame in the same moment, and made a vain attempt to put some order back into the place by stuffing handfuls of clutter into boxes. That’s when I found two books.

I picked them up and took them to the window for a look at them in better light, because among all of the crap that I had been digging through, among all the boxes of gaudy shirts and harmonicas and sheet music and condoms, they were the first books I had seen. One was a simple black notebook, in which a guitarist named F. Carlton Reeder had kept a daily log of his expenses. A typical entry might read “March 8, new A-string $.35, union dues $1.50, lunch with Mel $.75.” The journal began on January 1, 1957, and ended on what must have been the day his engagement at the Apollo ended and his belongings were put into escrow: November 6, 1957. I was alone, in a spooky old theatre full of ghosts in a spooky old town full of ghosts, holding the diary of a dead stranger, and the last entry in that diary was made on the day that I was born.

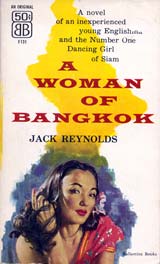

After that eerie moment I barely looked at the second book, but did see that the cover showed a lurid illustration of a vaguely Asian woman reclining on a divan wearing a low-cut gown slit up to her hip bone. A Caucasian male figure leered at her through a bead-curtained doorway, and that was enough to make me put the book in my pocket and take it along. Atlantic City no longer had a laundromat or hardware store, let alone a bookstore or public library, and I needed something to read. I took the appopriate letters downstairs and wrote “Three Stooges Film Fest” on the Apollo’s marquee, the second unit shooting crew came and got their shot and I put the letters back in the attic without cleaning up the mess I had made. For all I know, it remains that way to this day.

And when I got back to the hotel that night I began to read the novel. It was a first edition of Jack Reynolds’ classic Thailand romance A Woman Of Bangkok, and expecting as I was a tawdry bit of titillation, I was amazed to discover that it was a novel of extraordinary sensitivity and insight. The glue of the book’s binding had long since crystallised in the dry heat of the attic, and as I read my way through the book each page came off the spine like a dead leaf. When I finished the book I had a loose collection of three hundred yellowed, fragile pages held together with a rubber band, but I didn’t throw the book away.

One year later I was on a plane bound for Thailand. At thirty thousand feet over the north pole I re-read A Woman Of Bangkok in the brilliant white light of the stratosphere, and the man in the seat next to me must have thought I was crazy, to take such effort to read a thirty year old trashy novel that left a snow drift of crumbled paper in my lap with each page I read. By the time we landed the book was confetti, but that was okay. That book had laid in wait for my entire life, and after doing its job it disintegrated.

Since making my home in Thailand I’ve tried to find out everything I can about Jack Reynolds, which hasn’t been much. I’ve learned that he came here after running a fleet of ambulances for a Quaker mission in China through the 30’s and 40’s, and that he only produced one other book in his life: a collection of short stories about being a male midwife in rural China called Daughters of an Ancient Race. He married a Thai woman, had nine children with her, and eventually died. That’s all I know about the man who is responsible for my being here.

Mr. Reynolds’ single serious contribution to English Literature is about a young Englishman who falls in love with a Thai “dancing girl” in Bangkok circa 1950. She takes all his money, breaks his heart, costs him his job, and finally leaves him to a future of failure and bitterness. But despite its turgid content, the book is brilliantly written. It is a story full of wit, pathos and plain old human drama, and it’s one of my favourite books in the world.

Of course, the Bangkok that Mr. Reynolds described, where Patpong Road was only known to the airline pilots, doesn’t exist any more. It may never have existed outside of the author’s imagination. But if I ever do anything of any worth at all in this country, it will be due to Jack Reynolds writing about Thailand in a way that made me want to come here.

Books are more powerful than bullets or missiles, but they are almost impossible to aim. A book may not strike its target until decades after the author is dead, but it will rest on a shelf (or in a box) for years, always armed and ready to explode in someone’s head. All it takes is for one unsuspecting reader to trip over a book, like a Cambodian farmer tripping over an old land mine, to change his life forever.

Steve Rosse, formerly of The Nation and the Phuket Gazette newspapers, is a short story writer who evidences considerable depth of understanding of the Thai-Expat dynamic. His stories are alternately sweet and sardonic, lush with irony and, to use that old Portuguese word that doesn’t have an equivalent in English, saudade. Thai Vignettes (2005, ISBN 974-93439-2-1) is a collection of fiction and non-fiction stories, with a host of memorable characters and stories, most of which are fewer than six pages in length. Eight stories we found particularly compelling, none more so than the beautifully written and tragic Two for the Road. Don’t miss Rosse’s Expat Days: Making a Life in Thailand (2006, ISBN 974-94775-3-7), a non-fiction book reviewed on our History and Culture pages.

Its had a couple of poor reviews by guy’s who normally read comics and rely on pictures to tell them the story but is rightly up there in the classics of its time and still feels as fresh today as it did then I am sure.

This is a good blog. Keep up all the work.

I have an as new pristine copy for sale

Cool Article! My spouse and i had been simply just debating that there’s a whole lot absolutely wrong details on this matter and also you precisely replaced the belief. Many thanks for a marvelous contribution.